And so we come to the final of the "

classic" photographs of the Loch Ness Monster. By this I mean those black and white pictures which were the mainstay of Nessie books from 1934 right up to the end of the manic 70s and beyond. It began with the Hugh Gray photo of December 1933 and ended with the Peter O' Connor photo of May 1960. Colour photography came in but, strangely, the dramatic surface images dried up for 17 years despite the heightened attention from the good, the bad and the ugly (I exclude serial hoaxer Frank Searle from this observation).

These have been argued over and analysed with a fine toothcomb as believers and sceptics alike look for evidence to justify their stance on each photo. Eighty three years on, the claims of fraud, misidentification or genuine continue to this day. Six years on, this blog finally gets round to the final one - the H. L. Cockrell picture.

The time is also ripe to write this article for another reason - establishing contact with Herman Cockrell's son, Peter. A bit of detective work, sending off some letters and eventually Peter touched base some months back. Peter was a teenager at the time his father prepared for his Loch Ness expedition and he recalls helping with the equipment, the kayak and his father's enthusiasm and enjoyment for the whole project.

I am very glad to make his acquaintance and obtain material from him that helps form a fuller picture of his father and that expedition he made to the loch over 50 years ago. There is enough material for several articles, but first we focus on the main event.

THE MAN

Herman Louis Cockrell (or "Gus" to his friends) at that time ran a salmon fish farm near Dumfries in the

South of Scotland. But before that, he led a self sufficient life on a farm supplemented by his interests in gun punting, a venture that combined shooting wild fowl with a large bore gun on a punt, which was a flat bottomed boat with a square bow adapted to carrying the rather large punt gun used in commercial operations.

Shooting wildfowl provided an unpredictable income and food in a time of post-war rationing and austerity. But Herman was a man who loved adventure on the water and this led to his passion for building his own boats which is most clearly shown in the photo below of his workshop. In fact, the work in progress you see was the kayak for his Loch Ness expedition.

Reading his articles conveys a sense that his knowledge of aquatic animals overlapped into his speculations concerning

the Loch Ness Monster. For example, Herman Cockrell thought that the

creatures took to land not primarily for food, reproduction or anything

territorial, but rather to rid themselves of parasites. I find that an

interesting take on this particular aspect of Loch Ness lore.

Combining this with his natural ability to be inventive and come up with solutions led to the pursuit of his other interest in the Loch Ness Monster. Today, people such as myself just order what is required online. The

task of the monster hunter today is pretty much off the shelf,

multi-feature electronics. Back in 1958, what Herman Cockrell lacked in

products was made up for in practical ingenuity. The picture below shows Herman with the improvised camera he was developing for his one man kayak

search.

In the words of his son, Peter:

This began partly as a publicity stunt for the Solway

Fishery and partly “…just for the hell of it” but as time passed it became much

more serious and he put a great deal of mental and physical effort into the

project over a number of years. It appealed

very strongly to his curiosity, his sense of adventure and, very definitely, his

sense of humour. His idea, very

carefully thought out and executed, was to patrol the loch on calm nights when

any disturbance would be more visible on the surface and when, possibly, Nessie

would surface more readily. This

required a special craft, good photographic equipment and a means of verifying

results and of publicising his efforts whether or not he caught up with the

monster!

This was achieved as follows. An Eskimo kayak was built to give speed,

manoeuvrability and stealth on the water at night. The boat had steel frames to withstand a

close encounter with a possibly angry monster.

A well-known photographic company supplied two high quality cameras

which Gus built into a waterproof case with multiple flash guns and wiring

inside the boat. And finally “The Weekly Scotsman” provided

coverage and the use of their photographic labs to develop sealed film capsules

to counter any charge of faking photographs.

The construction of the camera housing exemplified the hands on approach to this whole affair.

In brief it was constructed from a paint tin

with a platform for the camera inside and a glass porthole soldered on the

front. A spotlight on top, made from a

cinema usherette’s torch, served as a view and rangefinder. The switchgear was held in a tobacco tin on

the side filled with glue to exclude water.

An expanding and waterproof rubber tube operated the shutter and film

winder. There were two flash bulbs on

the top in aluminium shaving soap containers plus two more on the bow of the

kayak mounted under cocktail glasses to protect them. It all worked well under test and then in

action on Loch Ness.

Leaving nothing to chance, Herman conducted night time experiments with his setup, as shown below. The equipment was ready, the game was afoot, it was time to head north.

However, as publicity for the expedition increased, the mention of explosives was made, and a degree of concern arose amongst parliamentarians which led to a

question being made to the Secretary of State for Scotland, John Maclay, on the 25th March 1958:

Mr. Hector Hughes asked the

Secretary of State for Scotland if he is aware that Mr. H. L. Cockrell,

of the Fish Hatchery, New Abbey, Dumfries, intends to explore the depths

of Loch Ness using a knife and explosives; and what steps he proposes to take to protect the amenities of Loch Ness and the fish in it.

Mr. Maclay: I

have seen Press reports of Mr. Cockrell's intentions. The use of

explosives might constitute an infringement of the Salmon and Freshwater

Fisheries Protection (Scotland) Act, 1951, and other statutes, but I

feel that this possibility can safely be left to the appropriate

authorities.

We can safely say that a bit of exaggeration cropped up in this entire mini-episode. As an aside, when

Peter O' Connor made references about bren guns mounted on canoes a year later; you can be sure this was merely a humorous play on what the media had got wrong concerning Herman Cockrell!

Moving onto the nitty-gritty of the story behind this picture and what better place to get it from than Herman Cockrell himself? As it turns out, Mr. Cockrell had been invited by The Scotsman newspaper to write a series of articles on his upcoming expedition to hunt for the Loch Ness Monster. That series ran from March to October 1958, culminating in the account of his famous photograph. I reproduce the relevant section below.

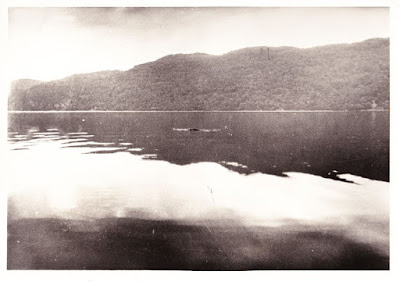

The night was very dark until the moon rose, the water calm with a slight swell, as usual coming from a direction completely unexpected. There was a little traffic on the shore. It was pleasant in open water, but the water was a bit colder after a storm. Just about dawn I had my first real test. A light breeze suddenly dropped and left me on a mirror surface about half way between shores with Invermoriston almost abeam to starboard.

Something appeared - or I noticed it for the first time - about 50 yards away on my port bow. It seemed to be swimming very steadily and converging on me. It looked like a very large flat head four or five feet long and wide. About three feet astern of this, I noticed another thin line. All very low in the water just awash.

I was convinced it was the head and back of a very large creature. It looked slightly whiskery and misshapen, I simply could not believe it. I was not a bit amused. With a considerable effort of will I swung in to intercept and to my horror it appeared to sheer towards me with ponderous power. I hesitated. There was no one anywhere near on that great sheet of water to witness a retreat but it was obviously too late to run. Curiously enough I found this a great relief. My heart began to beat normally and my muscles suddenly felt in good trim. I took a shot with my camera in case I got too close for my focus, and went in.

The creature headed slightly away, my morale revived completely. I had another shot and closed in to pass along it as I didn't want to be thrown into the air by a sudden rising hump or two. There was a light squall out of the glen behind Invermoriston, and the object appeared to sink. When the squall cleared I could still see something on the surface. I closed in again cautiously. It remained motionless and I found it was a long stick about an inch thick.

I thankfully assumed it to be my monster and took it aboard as a souvenir. I suddenly felt very tired and stiff and wanted my breakfast. The wind freshened. It can get quite choppy in ten minutes well offshore and I had a hard plug back to my camp in the flat cairn of the north shore. but I felt made. For the last few nights I had rather doubted my metal but I now knew I could do the job if necessary, because I really believed I had found the beast.

I arrived home and I really believed my particular monster was a stick - until the films were developed. The film showed things I had not noticed, either through fatigue of the night or - let's face it - the fright of the dawn. The film showed quite a large affair which had a distinct wash. There was no reason for this wash as the picture also shows the water mirror calm when the snap was taken by the reflection of the hills. What caused the wash? Could it have been Nessie after all? I just don't know.

Another point: the creature was seen by a Mr Brown and his wife from Invergordon next day in the same place but farther inshore. He describes it as "three big black humps churning through the water leaving a foaming trail, with 30 yards ahead of the humps a curious wake on the surface which seemed to be the leading part or head." We have never met and at the time no one knew of my own experience. Perhaps later I shall succeed. Anyway I cannot be accused of mistaking the monster for a stick - but it appears I mistook the stick for the monster.

Overall, the entire series is a fascinating account of one man's pursuit

of the monster and the resourcefulness employed in that endeavour. As I

read his story, I came to realise that Herman Cockrell was no ordinary

monster hunter for in more ways than one he epitomised the spirit and

adventure of that genre.

The two pictures Herman took can now be shown for the first time together and both uncropped. The first picture Herman took has never been seen mainly because newspapers tend to pick the best picture and ignore the others. Since Herman took the second photo closer to the creature, it won out. The first and previously unpublished picture is shown first followed by the more familiar shot.

I will look at these photos in more detail later; but what did he see and how did the various Loch Ness experts react? Naturally, various theories have arisen to explain what was in the second photograph. The first focuses on the stick mentioned in Herman Cockrell's account. Because Herman speculated that he may have mistaken the stick for what he initially took to be the monster, that has been seized upon by sceptics who then summarily dismiss the case. I will address the stick theory in the next section.

Of the main Loch Ness authors, Tim Dinsdale believed the picture was of the Loch Ness Monster (Herman's son sent me correspondence between Tim and his father requesting permission to print the photo in Tim's 1961 book). However, Tim is the only one I found that came out in support of the picture.

Others were non-committal, such as Nicholas Witchell in his "The Loch Ness Story", who says it "may" be one of the animals. Henry Bauer is also a "maybe" in his "The Enigma of Loch Ness". Other pro-Nessie authors make no mention of the photograph at all in their main works, such as Constance Whyte, Peter Costello and Ted Holiday. Whether that makes them pro, anti or neutral is not clear as sometimes I have found comments in minor works by authors which do not make it into their main books. For now, one must assume they are no better than neutral.

Which proved to be somewhat of a disappointment to me, but the stick incident seems to have muddied the waters too much for some. Indeed, if Herman Cockrell was non-committal in his initial public pronouncements, it is no shock that others have followed suit.

Of the critics, I was somewhat surprised that Maurice Burton does not mention the picture in his book, "The Elusive Monster". However, Ronald Binns is unequivocal in declaring it as a tree trunk (and first proposes that you can see through it). Steuart Campbell writes in his book that it looks like a stick, but in the end is not entirely sure what the picture shows. Nessie believer Roy Mackal concurs with the sceptics in his "The Monsters of Loch Ness" in identifying the object as a small log or stick.

A further search revealed that Maurice Burton did propose that Herman Cockrell was witness to his favoured vegetable mat in a 1982 article for the New Scientist. This mechanism causes vegetation to rise to the surface on the buoyancy of a build up of methane and, having discharged, allows this natural construct to sink out of sight. Today, this is a theory that has generally fallen out of favour in sceptical circles due to the eutrophic nature of Loch Ness. My opinion is that, even if true, an inspection of an area of water after the

eruption of a vegetable mat would surely leave more than just a thin

stick behind.

Going back to log theories, by proposing that a log was behind the photo, Ronald Binns was basically accusing Herman Cockrell of being economical with the truth (because he only reported a puny stick). In response to such log theories, Herman Cockrell wrote back to the Weekly Scotsman on the 6th November 1958 with these words:

The statement by the monk from Fort Augustus speaks of logs, floodwater and foam. But none of these were involved.

These are the main theories, now let us move onto a more thorough analysis of these pictures.

THE STICK

First of all, let us go back to the stick that seems pivotal to various commentators on this incident. Herman Cockrell described it as a long stick about an inch thick. When I asked his son, Peter, about it, his reply was:

I

do remember seeing the stick at the time because he brought it home.

It didn’t resemble the picture – it had some stubs of branches but was

basically quite thin and straight. I do not have any photos of it

unfortunately.

So

let us try and dismiss the theory that the object in the photographs is

a stick. I begin with my own experiments with a stick at Loch Ness a

while back. The photograph below shows the stick for this simple

experiment. It was about three feet long and at least an inch thick.

The

procedure was simple. Throw the stick into the loch and take some

photographs of it. I leave it to the reader to figure out where the

stick is in the photograph. It was no more than 10 metres from me.

Just

in case a black and white photograph may enhance the appearance of the

stick, I include such a version below. Admittedly, the light levels

would have been lower for Herman Cockrell, but I see that as a stronger

argument that the object in the photos is not a stick. For your

information, the stick is just left and above of the centre of the

picture.

In

fact, I would have been at a more elevated position than Herman would

have been in his canoe. Again, that would make the stick more visible

for my pictures than it would for Herman's situation. Based on this experiment, I would conclude the object in the photograph is unlikely to be a branch of four foot length and one inch thick.

One

other aspect of the stick theory I would like to address is the idea

that the better known version of the Herman Cockrell photo shows a gap in

the object, thus suggesting it is indeed a log or stick. This is shown in an

enlargement of the object. You can see a lighter region on the left side of the object.

There

are three reasons I wish to advance as to why this is not a convincing

view. Firstly, the stick, as described by Herman Cockrell and his son,

does not sound like a stick that would create a gap. It was

long and thin and that, to me, means no possibility of a gap between it and the water.

Secondly,

Herman Cockrell himself, suggested that what is seen is no more than a

wave briefly hitting the object. I quote again from his letter to the

Weekly Scotsman of 6th November 1958 where he briefly speaks of the

trouble he had with his photographic setup:

The spotlight for view finding was no use after dawn so I had to

improvise by holding the camera up and viewing through a tiny hole under

the light case. This may be why I missed the splash that appeared

during the taking of the snap.

The third reason can

be deduced from the now available first photograph. As you can see

below, a zoom in of this picture shows no indication of a gap between

object and water. Based on these three arguments, I would suggest the

light area is indeed a splash which, by consequence, reinforces the idea

that this was an object more substantial than a stick.

Realising that the stick theory was in troubled waters, W. H. Lehn, an electrical engineer from the University of Manitoba, attempted to salvage the theory by proposing that the appearance of the stick had been visually exaggerated by a temperature inversion creating mirage conditions. You can read his 1979 article at this

link. Though this theory may have some merit for vertical objects, I was not convinced it did for a low lying, horizontal object showing no more than half an inch above the water (assuming such mirage conditions actually prevailed at the time).

By way of example, Lehn demonstrates the mirage effect on a near vertical stick on Lake Manitoba where the temperature layer difference was at a maximum of 25 degrees centigrade (way above Herman Cockrell's environmental conditions). Viewed at a distance of 10km, the stick can be seen at one point to vertically distend to double in apparent height. A doubling of half an inch of stick is hardly going to constitute much on any photograph.

However, Herman Cockrell only had about 20m of potential temperature inversion to look through compared to the much more distortive effects of 10km of such atmosphere. Moreover, an examination of the better known photograph shows no evidence of a mirage. There is no indication of the surrounding waters being distorted or the distant shoreline.

In concluding this section, perhaps a comment from Herman Cockrell's account may explain the role of the stick in the whole affair:

It looked like a very large flat head four or five feet long and

wide. About three feet astern of this, I noticed another thin line. All

very low in the water just awash.

May I suggest that the "

thin line" seen was the stick. I can't prove that, but if it was in close proximity to the creature, it would have registered a small visual presence.

FURTHER ANALYSIS

That the picture was taken at the location specified is in no doubt as this image from Google Street View shows. The hill contours from left to right match those in the second photograph taken. Mind you, no one was seriously doubting that Herman Cockrell was where he claimed to be.

Now having both photographs available for analysis allows new information to be extracted. The main question is whether the object in question moved of its own accord? By examining the shorelines in the two pictures, correlation points can be identified. Two such points are circled on the two pictures below.

As you can see, the object has moved in relative terms from the right of the two reference points to the left of them. But the difference between the two pictures is the combination of both the movement of the object and the kayak. The movements between the two shots are described thus by Herman Cockrell:

I took a shot with my camera in case I got too close for my focus, and went in. The creature headed slightly away, my morale revived completely. I had another shot ...

Merging the two photos over the two reference points give us the following composite showing the relative motion of the creature. Note Herman's reference to the object as a "

creature" in this quote and herein lies his ambiguity. A stick may move along with the prevailing south western wind up the loch, but Herman's language does not suggest an object driven by external forces. The phrases "

it appeared to sheer towards me with ponderous power" and

"the creature headed slightly away" suggest Herman witnessed a degree of self propulsion in the object under view.

Critics may take it as read that Herman Cockrell stated he merely saw a stick, but his ambiguous language, such as referring to the object as the "

creature" suggests otherwise. In fact, given what I have said about his experience on various waters, Herman Cockrell strikes me as a man well equipped to judge the movement of objects on water. He had spent many a time on his own home waters in pursuit of his punt canoe and even describes himself as a "

sailor" to Tim Dinsdale in one of their correspondences.

My own judgement is that the relative positions of the object in the composite suggests a motion not accounted for solely by wind or Herman's cautious approach to the object. That would suggest an object possessing a degree of inner motion.

The object itself presents what is a mainly uniform dome shape in the tradition of the single hump sighting. If the width of the object is the maximum of five feet stated by Herman, then the maximum height is about 10 inches out of the water. Is this symmetry evidence of a living object? I would say so, certainly it is not consistent with the shape of tree debris.

What is perhaps of equal interest is the whiteness surrounding the object. This is contrasted with the darker tones of the hills being reflected on the surface of the water. This is most likely an area of water disturbance around the object. It is evident around the object in both photographs which suggests it is a phenomenon associated with and generated by the object.

The extent of the disturbance is not as symmetric as the object itself as the disturbance extends an apparent distance of about 7.5 feet to the left of the object and about 10 feet to the other side. My own interpretation is that this is in fact the bow wave of the object generally moving in the direction of Herman Cockrell. If the creature is heading towards you at near water level, then the disturbance caused by forward motion will look a horizontal line of turbulence.

That this situation is intimated by Herman himself is again exemplified by the phrases, "swimming very steadily and converging on me" and "it appeared to sheer towards me with ponderous power". Furthermore, the phrase "the creature headed slightly away" before he took the second photograph would also imply that the furthest arm of the bow wave would undergo a degree of foreshortening in the picture, and this is what we get with the left arm being 25% shorter than the right arm. The first photo, though more indistinct in showing the wake, suggests more equal bow arms.

Finally, there is a suggestion of another object about 10 feet to the right of the main object in the picture. It is somewhat spherical and has a maximum extent of 8 inches. It is visible in the second, well known picture, but is not visible in the first picture. What this might be would be a matter of speculation on anyone's part. Is it physically connected to the main object under the surface or is it completely unrelated?

For me, there is just not enough information to favour one explanation above another. However, I would say that if the object is heading towards Herman Cockrell, then the object on the right is not likely to be the head.